Ask the sky and explore unceasingly - Outlook of the global space industry

What does the year ahead hold for the global space industry? Richard Lowe provides some insights on behalf of the Royal Aeronautical Society Space Division.

They say air travel brings the world closer together. Perhaps the same can be said of space travel? In 2024, we can expect an increasing number of space tourists, moon missions, and services from speeding machines. However, it is worth noting that there are already more than a million satellites registered with the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) for launch by 2028 (up from fewer than 500 in 2018). Our space neighborhood is starting to feel a little small.

Fly Me to the Moon

带我飞向月球

It is often said that any landing you can get out of safely is a success, and to prove this point,Chandrayaan-3Take off and land again - almost half a meter away from the original landing point.

The next challenger to the moon is Japan's Smart Lander for Investigating Moon (SLIM) mission, which is still en route at the time of this posting and is scheduled to land in early 2024.

Looking back at 2020, China's unmanned Long March 5 mission made the country the third country to return to Earth from the lunar surface and bring back material samples. A "backup" spacecraft was built at the time, which will now fly in 2024, namely Chang'e 6, which aims to bring back samples from the far side of the moon for the first time. The far side of the moon has a very different geological history from the near side, with a greater density of impact craters, and earlier observation missions have confirmed the difference in material composition. If successful, the samples will return to Earth in 2024.

Also worth noting is NASA's return to the moon, or at least to space near the moon, in 2024. Artemis II aims to take humans out of low Earth orbit (LEO) for the first time in 50 years, with four astronauts flying over the moon and returning to Earth. If all goes well, the subsequent mission (Artemis III) will land on the lunar surface in 2026.

Learning to Fly

学习飞行

The launch sector faces some challenges in 2023. Europe's Vega C remains grounded, Virgin Orbit has fallen into bankruptcy, and the first flight of Ariane 6 has been delayed until 2024. The once vibrant Russian launch sector is now in decline. Japan's new H-3 launch vehicle also failed on its first flight, losing the Advanced Land Observation Satellite (ALOS-3) it was carrying.

SpaceX is now the undisputed launch leader in the world, having completed around 80 Falcon 9 missions. Europe as a whole has only had three launches. It is unlikely that Ariane 6 will fill that gap. Many are looking to SpaceX’s reusable launches to drive down the cost of space access, but a monopoly can set its own price. Will we see the first (successful) launch from the UK in 2024?

Come Together

汇聚一体

The next new area to focus on is In-orbit Servicing and Manufacturing (IOSM). This term covers a wide range of activities including orbital tugs, inter-satellite inspections, in-orbit assembly (for larger structures), and many other services, including the manufacturing of high-value materials. Many of these activities rely on satellites orbiting in close proximity to each other.

With few exceptions, the current space industry is still based on single-use satellites that must fit into the dimensions of a launch shroud. The failure of a local component can render the entire spacecraft useless, and the concepts of “upgrades,” “life extensions,” or “repairs” are foreign. In-Orbit Servicing and Manufacturing (IOSM) will change this and more.

Space debris cleanup services were among the first movers. The FCC hit a milestone in 2023, issuing its first fine for littering in space. Satellite operator DISH failed to adequately clean up at the end of its EchoStar-7 mission, resulting in debris that came close to one of the main commercial orbits (the geostationary “belt”). The $150,000 fine was relatively small for a company the size of DISH, but the FCC sent a clear message, urging the industry to take space sustainability seriously or face reputational and financial damage.

It is encouraging to see the UK Space Agency and its parent body, the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT), also taking action in this regard. Recent government action is supporting the sector and the UK has a vibrant start-up community, but it is a fragile lead.

The UK’s success in the new IOSM sector will require investment in national capabilities and strong international collaboration. Pioneering companies such as Astroscale, Space Forge, ClearSpace, D-Orbit and OrbitFab have all chosen to locate at least part of their operations in the UK.

While some may question the market for these new services, consider that each orbital service has a dual application. Satellite visual health check? In-orbit assembly? The National Reconnaissance Office will certainly value the capabilities of new telescopes that cannot fit into a single launch shield.

If you can re-orbit or de-orbit your own satellite, then you can also operate on someone else’s satellite. Many space technologies have found early sponsors in the “national security” arena. IOSM will be no exception. The world’s space powers will not wait for the commercial community, nor will they outsource this capability.

These capabilities will be central to launching in and out of space. Europe’s launch sector did not foresee the changes ahead, and SpaceX built one from scratch with reusable rockets. Space tourism could have happened in Europe, but it didn’t (Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic in the UK cornered the market first, but it came from the US). Advanced orbital capabilities are coming to a space power near you – ready or not.

Accross the Universe

横跨宇宙

The target asteroid, named Dimorphos, did change its orbit slightly when it was hit. Of course, more insightful results were achieved. DART self-destructed, but it helped reveal the composition of the asteroid and how its surface responded to the high-speed impact.

In 2024, the European Space Agency will launch a follow-up mission called Hera. This mission will return to the same asteroid to observe the impact site and its scattered debris in detail. At the same time, it will also conduct a series of capability demonstrations, including deploying tiny "nanosatellite" deep space helpers near the asteroid, carrying additional scientific sensors. Hera is expected to reach the impact site in 2026.

Other notable exploration missions for 2024 include NASA's Europa Clipper, which is scheduled to travel to the Europa system in 2030. Japan has its sights set on Mars. The Mars Moons Exploration (MMX) robotic mission aims to bring back surface samples from Mars' tiny moon Phobos, which is only 22 kilometers in diameter and therefore has a very weak gravitational field. Therefore, returning to orbit from its surface requires much less fuel than from Mars itself.

However, the mission could face significant delays. MMX will be launched on Japan's new H-3 rocket - which has suffered setbacks in early flight tests. If it misses the 2024 launch window, it could be delayed by two years, waiting for the next Earth-Mars orbital transfer opportunity.

Take Me Home

带我回家

At the end of 2023, the government established a new National Positioning, Navigation and Timing (PNT) Office within the Department of Science, Innovation and Technology, with the aim of "improving resilience and driving growth". Does this mean that a national satellite navigation capability is back on the table? Not really, but it is a start, and with the creation of the PNT Office, navigation has finally found a solid home within government.

As we head into 2024, progress has already begun. Initially this may involve developing a plan to manage national navigation crises. In addition, various technical and organizational measures can be taken to make crises less likely, more localized, and enable faster recovery when systems such as GPS experience problems.

Global navigation underpins vital industries such as transportation, energy distribution, financial systems, law and order, and construction, not to mention national defense. In this regard, national resilience is in everyone’s interest.

We've Been Observing

我们一直在观察

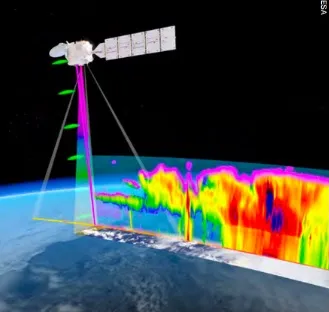

ESA/JAXA EarthCARE atmospheric monitoring mission to launch in 2024 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

EarthCARE, a 2.5-tonne atmospheric monitoring mission developed jointly by the European Space Agency and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, is set to launch in 2024. With Europe's Vega C launcher out of commission and Russian services out of reach, the European Space Agency has turned to SpaceX's Falcon 9 to get EarthCARE into orbit.

Meanwhile, the critical strategic and operational role of space surveillance remains evident in Ukraine. Throughout 2024, we can expect both sides to receive new intelligence from orbit every day—whether it’s heat maps of artillery activity, detecting new fortifications and enemy movements, or collecting graphic evidence of war crimes. Ukraine will continue to rely on a number of important resources, including Western Earth observation capabilities. In a future conflict between great powers, space capabilities (referring to the capabilities of a country or organization in the field of technology, equipment, personnel, etc. in the space domain) may not determine whether the battle is won or not—but the lack of space capabilities will be the loss of the ability to fight. Those orbital assets themselves will become targets of war. Gaining influence in orbit—defending, maintaining, monitoring, and subverting satellites—is the entity of cyber warfare.

I Just Called

我想建立联系

Orbitfab is one of the IOSM companies that has chosen to establish at least part of its operations in the UK. It specialises in providing spacecraft refuelling services.

Commercial satellite communications from LEO are now in the "proven" phase. OneWeb's services are widely available by the end of 2023, and SpaceX's Starlink program has been making headlines for some time.

Will these services be financially successful? It's hard to tell right now. Starlink achieved "breakeven" in late 2023, but its user growth has been much slower than previously forecast. Starlink offers internet service for more than $1,400 a year. But it's clear that only people who can't find suitable service locally will sign up. Still, it could still have an impact on the business of traditional geostationary satellite communications providers.

Commercial success aside, Ukraine’s experience shows that Low Earth Orbit (LEO) communications can be a valuable tool for national defense. SpaceX recently won a contract to develop Starshield, a cyber-enhanced military version of Starlink (meaning thousands more satellites in orbit).

A redesigned military version of Starlink also shows further potential. Use a communications signal in the right way and you have a global navigation service. Take a giant constellation of receivers in orbit and you have a global persistent signals intelligence (SIGINT) system. Spire Global already uses signals intelligence for commercial purposes, albeit with a much smaller constellation of satellites monitoring transponder signals at aviation and maritime locations.

In the UK, the Skynet 6 project is underway. This is the Ministry of Defence's next generation secure satellite communications capability, which will cost £5 billion over ten years and is the UK's largest space project, even larger than the UK's investment in the European Space Agency.

An earlier move -- in the form of Skynet 6A -- was to fill the gap left by the earlier Skynet 5 satellites that were about to retire (and/or tank). That launch was expected in 2025. Then, in early 2023, Babcock International was awarded the contract to operate Skynet's "package delivery" mission (which came as a surprise to many).

Attention now turns to the competition for the “persistent capability” (SKEC) portion of the program. SKEC will deploy multiple geostationary satellites for broadband and narrowband communications. One of the many challenges facing the UK government is to create a viable competition for delivery while keeping money, technology and jobs in the UK. But such procurements rarely come about, and it’s difficult to maintain a healthy and competitive domestic supply chain. Perhaps the next generation of Skynet satellites will be refuelable?